Digital Twins: A Smart Fix for South Africa’s Water Woes

Digital twins offer powerful tools to improve the maintenance of South Africa’s water treatment plants. However, their success depends on skilled human expertise to interpret and act on the data, experts from Stellenbosch University point out.

The root cause of water supply outages in South Africa’s municipalities is well-known: poor or non-existent maintenance of critical infrastructure. This manifests through water gushing from damaged pipes, flooding roads, malfunctioning pumps, or wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) that are barely functioning, among others.

There are reports that consumers in some other African countries have it worse — but that’s cold comfort. South Africa’s crisis is unique and must be addressed urgently and head-on.

Need for Cost-Effective Strategies

As authorities explore cost-effective and sustainable maintenance strategies to tackle the problem, it is worth considering the opportunities that technological advances are opening up. One area with huge potential is integrating digital twins, suggests Emeritus Professor Anton Basson of the Department of Mechanical and Mechatronic Engineering, Faculty of Engineering at Stellenbosch University. He also serves as Rand Water Chair in Mechanical Engineering.

Prof Basson has researched digital twins extensively and developed models for deployment in water treatment plants to support critical maintenance functions. Drawing from experience, he sees the versatility of digital twins presenting a compelling case for their integration in maintenance programmes.

The Role of Digital Twins

The convenience that digital twins (DTs) bring to the maintenance of wastewater treatment plants lies in their versatility. In this area, DTs can play various roles, including:

Predictive Maintenance

a. Predictive Maintenance

“DTs can aid the development of predictive maintenance models, which require substantial historical operational and maintenance data. Once the model has been developed and is deployed for routine use, a DT can host the model and feed it with live data. Then, with data curation, it can handle missing values or outliers and communicate the model results to stakeholders,” Prof Basson explains. However, he adds that for long-term use, the predictive maintenance model itself must also be maintained. For this purpose, DTs can facilitate “machine learning operations” (MLOps), enabling continuous development and continuous integration (CD/CI) of predictive maintenance models.

b. Monitoring through Comparing Operational with Expected Parameters

DTs can also support other maintenance-related tasks. A monitoring DT (of which a predictive maintenance DT is one example) can continuously compare operational parameters with expected parameters, as defined by various models. These models can be machine-learning-based, physics-based, statistics-based, or a hybrid of these approaches. Examples include monitoring pump-bearing temperatures and vibration levels, comparing pump performance with manufacturer specifications, and comparing pressure and flow rates in distribution systems to detect leaks.

Monitoring through Comparing Operational with Expected Parameters

b. Monitoring through Comparing Operational with Expected Parameters

DTs can also support other maintenance-related tasks. A monitoring DT (of which a predictive maintenance DT is one example) can continuously compare operational parameters with expected parameters, as defined by various models. These models can be machine-learning-based, physics-based, statistics-based, or a hybrid of these approaches. Examples include monitoring pump-bearing temperatures and vibration levels, comparing pump performance with manufacturer specifications, and comparing pressure and flow rates in distribution systems to detect leaks.

DT Design for Water Treatment Plants

The complexity of water treatment plants renders the design of their digital twins challenging. Every asset is unique, so the first design must be meticulous. What are the initial steps to consider?

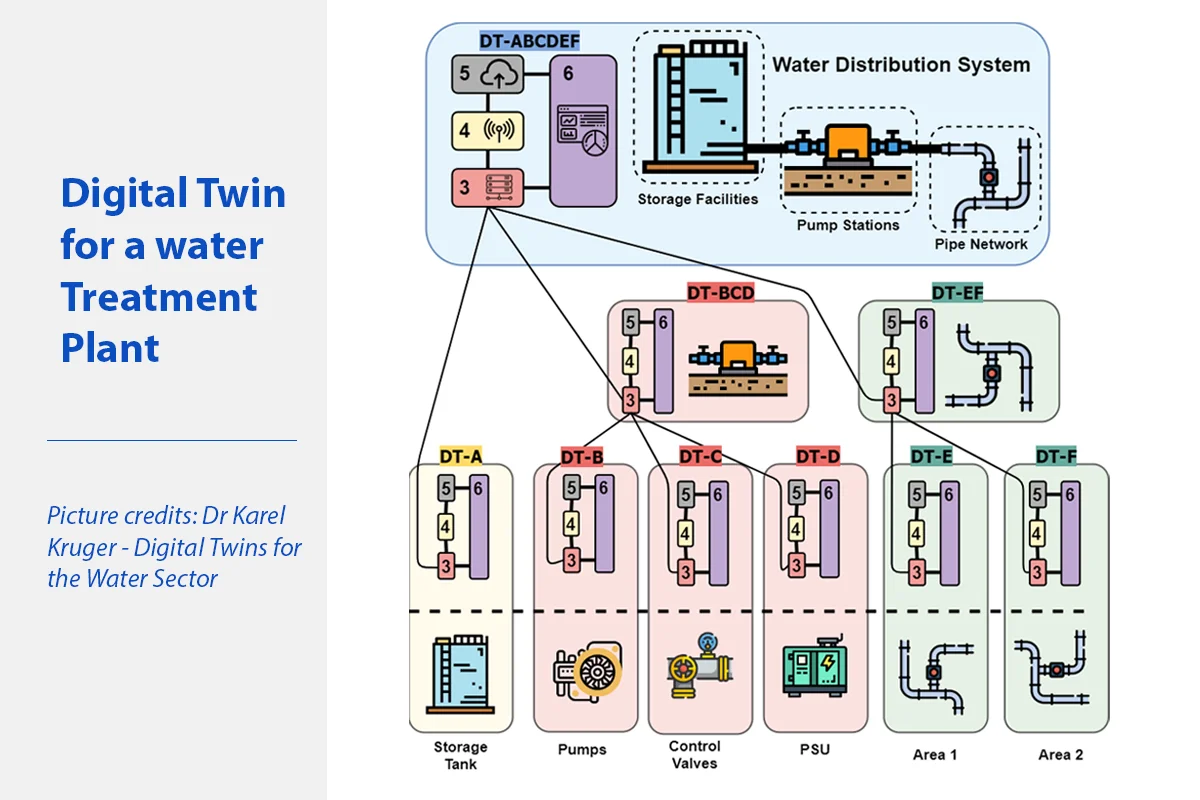

According to Prof Basson, since DTs are engineered systems, a systems-engineering approach is a good way to develop and maintain them. “The key starting points include: determining who the stakeholders are for the DT system, what their needs and expectations are, how the physical system can be decomposed, and the nature of the data that can be drawn from the physical system.”

Ramjack is the provider of remote equipment monitoring solutions and technology integration services to various industries worldwide. The company considers Africa as one of its biggest markets.

Data Integrity and Quality

Once the relevant parameters have been incorporated into the design, the next step is ensuring the integrity of the collated data. Prof Basson describes data integrity and quality as major concerns in data-rich systems like digital twins and predictive maintenance. “Data anomalies can be difficult to distinguish from process anomalies. An unexpected sensor reading — such as a high bearing temperature — could be due to a faulty sensor. There may be a fault in the temperature probe or in the signal path between the sensor and the DT, or the system being monitored could genuinely be faulty (e.g., the bearing is failing).”

Monitoring Data Quality

To minimise anomalies in data, monitoring data quality is essential. The challenge, however, is that monitoring data quality is a task similar to monitoring the system itself.

To manage this situation, DTs can typically use rule-based, statistics-based, and machine-learning models to detect and potentially correct anomalies, Prof Basson suggests. However, he adds, “This is not yet an exact science. Explainable anomaly detection and correction is an active research field in the machine learning community.”

Longevity of the DT

Assuming the DT is functioning, what adjustments can be made to keep it closely aligned with the water treatment plant, especially considering these plants are built to last for decades?

“The longevity of DTs for long-lived physical systems is an active research field,” Prof Basson explains. “The DT itself must be monitored and adapted as well. For example, we’ve published research on DTs to monitor predictive maintenance pipelines and IoT devices. Our approach involves keeping DTs highly modular to simplify their own ‘maintenance’.”

Not a replacement for human expertise

Granted, digital twins can facilitate predictive maintenance in remarkable ways. Nonetheless, they can’t replace competent personnel, cautions Prof Kobus du Plessis of the Civil Engineering Department, a specialist in municipal water matters.

He asserts, “The main challenge is a shortage of trained expertise, supported by appropriate maintenance budgets, that can effectively manage water treatment works. Wastewater treatment works (WWTWs) are biological factories that require thorough knowledge of biological degradation processes and, specifically, disinfection.”

This underscores the need for training at various levels, a need already recognised in legislation. Unfortunately, there are rarely enough bodies or sufficiently trained individuals to meet it.

Prof Basson concurs: “The reality is that DTs and humans need to complement each other. DTs are excellent at integrating information from multiple sources to provide context-rich insights. Often, humans are still key to interpreting this information. In some cases, predictive maintenance models can detect patterns that are too complex for humans to see.”

On the other hand, experienced humans can use tacit knowledge or information not available to DTs to make nuanced deductions that may be difficult (or too expensive) for DTs to replicate. The ideal, Prof Basson recommends, are experienced humans working in tandem with DTs that provide context-rich data.

The long and short of it: To get the most out of digital twins as one approach to solving the country’s water supply crisis, South Africa needs skilled personnel. But there is no doubt that digital twins can be a smart fix for the country’s water systems if used properly.